VGM losses are approximately US$6bn, but who’s counting?

Cargo losses as a result of improper weight declarations for cargo carried in containers were meant to have been solved with the introduction of the Verified Gross Mass (VGM) regulation in 2016. But cargo accidents since the introduction of the rule show that it can be ineffective.

The loss of more than a hundred containers from CMA CGM George Washington two years ago is evidence that there is some way to go before the regulation is completely effective, while the major loss of 342 containers from MSC Zoe in 2019 could also prove to be yet another major container incident caused by container weight issues.

VGM non-compliance is an urgent issue for the industry because, apart from the safety element of the rules, which is self-evident and must be the number one priority for the industry, the economic impact of such accidents is also a material consideration.

Shipping accidents, caused by VGM non-compliance and misdeclared containers, can financially affect all the stakeholders in the transportation process, including shippers, lines, port/ terminal operators, insurance companies, all the way along the supply chain to truckers and retailers.

It is estimated that the transport and logistics industries lose more than US$6 billion annually due to poor practices in the overall cargo transport unit (CTU) packing process, sources confirmed to Container News.

Peregrine Storrs-Fox, risk management director of TT Club, clarified that it is almost impossible to get a full appreciation of the costs incurred because of the absence of a standardised and detailed reporting mechanism through either shipping or insurance.

“We have no consolidated source of data for such matters,” an industry expert agreed. “IMO struggles with the same issues for casualties. VGM is massive, the weight discrepancies require hours to sort out for just one unit and build a case on,” he said.

However, there are an important number of stakeholders within the industry who say that they are completely familiar with VGM regulations and that the regulation is operating satisfactorily.

“VGM is not really an issue anymore,” said a spokesperson from the German line Hapag-Lloyd. He believes that the regulation is accepted across the industry and no longer poses problems, adding that “It has become a normal thing that is part of the supply chain and vessel operations.”

An office manager of a freight forwarding company expressed the same view that all parts of the industry have become very familiar with the new situation and proceed with the whole stuffing of the container without experiencing problems.

At the same time, Kathryn Oldale, Head of Strategy, Policy & Communications of DB Cargo UK confirmed that the rail freight company has seen zero impact since the introduction of VGM.

However, even though the VGM regulation was a significant step forward, there are still some blurry spots in the container packing process, and the industry must focus on these issues to sharpen its image through improved safety and efficiency.

Notwithstanding these views, many in the sector would like to see improvements in the enforcement of regulations, which would increase the rules’ effectiveness.

One reason that the regulations may be difficult to police is that there are different methods for calculating the weight of containers. In part, this is because the system is populated with stakeholders that have a varying level of wealth to invest in equipment and processes such as weighbridges.

If a port or terminal is lucky enough to have a weighbridge the calculation is straight forward. The container along with its cargo contents is weighed with a deduction for the weight of a truck and its fuel. This can be arranged by a shipper or a third party.

However, for those facilities that operate without the benefit of a weighbridge the calculation can be more complex. It involves weighing all the packages/cargo items and contents (including securing equipment/dunnage) before it is packed into the container by means of a certified method approved by the competent authority.

When each item has been weighed the totals will be aggregated to the container’s tare weight shown on a label on the container.

While this calculation helps those without the means to weigh containers, it can, however, create difficulties for shipments where multiple consignors are involved.

Potential dangers

To begin with, it is important for everyone to realise the real jeopardies of a misdeclaration of containers. Peregrine Storrs-Fox explained the potential dangers of a misdeclared container weight and conceded that there have been cases in which discrepancies between the weight declared and actual weight have been reported following the checking process.

The considerations of the involved stakeholders are the mistakes in the declaration of gross mass and content, load distribution and classification of cargo. Errors in the above processes can potentially lead to accidents, including the damage or even the loss of containers.

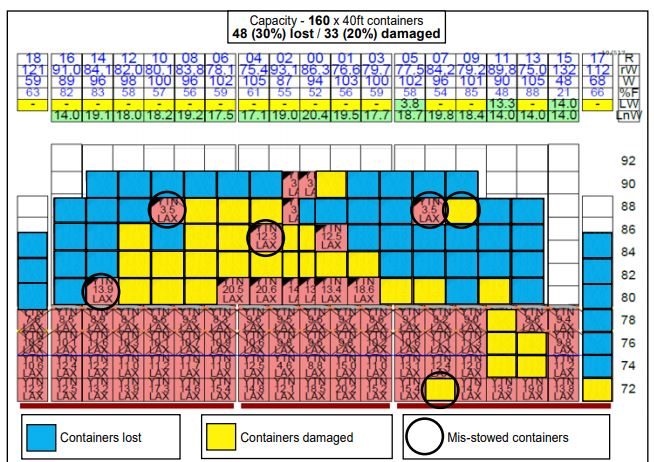

In an incident that occurred on 20 January 2018 the CMA CGM George Washington is probably the most indicative example of the disastrous effects of VGM non-compliance. The serious accident on the 14,414TEU container vessel resulted in the loss of 137 containers and the damage to another 85 boxes.

“The UK-flagged container ship CMA CGM G. Washington unexpectedly rolled 20° to starboard, paused for several seconds, then rolled 20° to port,” the UK’s Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) reported two years later in the summary of its Accident Investigation Report published on 16 January 2020.

The containers loaded on board CMA CGM G. Washington in China were weighed, and their weights recorded by the terminals during the loading process. The terminal weight data was not used to check the accuracy of the containers’ declared VGM and there was no process in place to do so, according to the MAIB.

Following the accident, the terminal weight data recorded at Xiamen (2,469 containers) was obtained and compared against the declared container VGM data.

The data analysis identified that:

- The total terminal weight for the 2,469 containers (30,394tonnes) was 736tonnes (2.4%) lower than the total declared VGM.

- 65% of the containers’ VGMs were within +/- 5% of the terminal weights.

- Of the remaining 35%:

- 2% were over 1tonne heavier than their declared VGM, with the largest variance being 16tonnes.

- 10% were over 1tonne lighter than their declared VGM, with the largest variance being 8tonnes.

Containers loaded in Xiamen were present in bays 18 and 58, but none were stowed in bay 54. Bays 18, 54 and 58 had all collapsed during the accident.

MAIB highlighted several safety issues including the reduced structural strength of the non-standard 53ft containers (16.15 metres long, 2.896 metres high, 2.59 metres wide), inaccurate container weight declarations, mis-stowed containers and loose lashings.

The report concluded that:

- bay 54 collapsed because the acceleration forces generated during the roll exceeded the structural strength of the non-standard 53ft containers stowed there

- bay 58 failed because some of the containers were struck by the 53ft containers from Bay 54 as they toppled overboard

- bay 18 failed as a result of a combination of factors but was probably initiated by the failure of one or more of the containers stowed there

MAIB mentions in its conclusions that the ships’ teams and central cargo planners were unable to access container CSC (International Convention for Safe Containers) information concerning individual types of containers, their dimensions, strength, and inspection status prior to loading.

The UK government organisation suggests that “access to a fully populated Bureau International des Containers, Global Container and Approved Continuous Examination Programme databases would address this issue.”

Before the CMA CGM George Washington accident and one of the reasons for the introduction of the VGM rules was due to the fact that accidents such as the Annabella were occurring too regularly.

The specific incident was almost nine years before the VGM regulation was enacted. It does manifest, however, why the shipping industry needed a framework of regulations to manage the container weighing and packing situation.

The Annabella, managed by Döhle (IOM) Ltd., suffered a collapse of cargo containers on 25 February 2007. According to the MAIB investigation into the accident, published in January 2015, the 868TEU boxship encountered heavy seas which caused the vessel to roll and pitch heavily during that evening.

On the morning of the next day, the crew discovered that a stack of seven 30ft cargo containers (9.12 metres long, 2.44 metres wide and 2.59 metres high) in bay 12, number 3 hold, had collapsed against the forward part of the hold. This resulted in damage to the containers, the upper three of which contained hazardous cargo.

MAIB reported that the collapse of cargo containers occurred as a result of downward compression and racking forces acting on the lower containers of the stack, which were not strong enough to support the stack as their maximum allowable stack weight had been exceeded and no lashing bars had been applied to them.

“As a result of its analysis of this accident and the ascertainment of its causes and circumstances the MAIB considers that there are shortcomings in the flow of information relating to container stowage between the shippers, planners, the loading terminal and the vessel,” the UK government body claims in the report.

“While the industry recognises that the master must approve the final loading plan, in practice the pace of modern container operations is such that it is very difficult for ship’s staff to maintain control of the loading plan,” added MAIB, establishing the serious issues that VGM regulation was supposed to solve 10 years after the accident and one and a half years after the report.

Moreover, commenting on the stacking weight of the boxes, MAIB mentioned that “the presence in the transport chain of containers that have an allowable stacking weight below the ISO standard should be highlighted by appropriate marking and coding.”

However, the main causes of the Annabella accident, which occurred prior to VGM, are recognisable in the MAIB’s report on the George Washington, which happened nearly two years after VGM was introduced. And it is possible that the investigation into the MSC Zoe which was involved in an accident in January 2019 could come to similar conclusions to those found in the Annabella and Washington investigations.

The huge loss of approximately 342 containers, with a further 1,047 damaged, on the MSC Zoe, in the North Sea is still under investigation.

The 18,400TEU container vessel was en route from the Port of Sines in Portugal to Bremerhaven in Germany, which led to one of the biggest containers’ losses in history.

In an interim report published jointly by the German Federal Bureau of Maritime Investigations and the Dutch Safety Board, the investigation found, “The swell came from abeam port and the MSC Zoe rolled 5-10° towards every side [sic] in heavy swell.” The report continued to say that the north-north-westerly winds blew with a force of 8-10 on the Beaufort scale creating waves of 5.5m in height with a 12-13 second wave period.

Final conclusions on the MSC have yet to be made, and there are a number of theories as to the cause of the loss including issues of routing, North Sea topography and inadequate lashing, but until the investigation, led by Panama as the flag state, with support from both Netherlands and Germany, come to an end, there is no certainty. Even so the similarities between the Annabella, CMA CGM George Washington and MSC Zoe are striking.

Tragedies caused by VGM non-compliance can lead to costly litigation and pollution. It is, therefore, essential to explore its background causes that have led to these losses with a view to learning from the mistakes of the past.

The secretary of the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) Container Panel, George Charalampidis, responding to a Container News request, said that not all ports and terminals are capable of properly managing the VGM regulations, because of the lack of resources.

“There is some anecdotal information that suggests that not all ports and terminals have the resources and ability to check that VGM is properly declared and cases where, while no such lack of resources exists, mis-declared VGM still occurs,” he pointed out.

It is not clear which precise ports and terminals lack the resources and cannot cope with the VGM regulations, but the most likely locations for the investment difficulties are in developing countries where resources are scarce.

“This situation is always going to be the case,” agreed captain Richard Brough, head of the International Cargo Handling Coordination Association (ICHCA).

In an ICHCA survey, its members, which include some of the largest port and terminal operators in the world, such as APM Terminals, DP World, PSA and Associated British Ports, said that if legislation forced them to weigh containers, the industry would grind to a halt.

There are some ports and terminals, Brough explains, that handle millions of TEU per annum, but did not have a working weighbridge, or certainly not a convenient one. “Weighbridges themselves are problematic, what about 2 x 20s? You have to make several trips,” he continued.

If there is a lack of resources and significant areas of the industry itself are unwilling to make changes the need for regulation is clear, so that all stakeholders are operating under the same restrictions with similar costs.

The investment needed to make VGM effective would have been apparent from 2016 when the regulations were enforced. As confirmed by captain Brough who said, “The industry had to invest huge sums to gear up [for the VGM regulations].” However, he added, “Some stakeholders have not invested yet.”

It is understood that as the major obstacle to an efficient VGM system is the lack of port resources and not the unwillingness of the ports to comply with Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and VGM regulations, the industry must find a solution to the investment difficulties and make sure that the regulation is properly and uniformly enforced.

“Many countries are struggling with scarce resources and rely on the industry to police itself or ‘buddy’ down through the supply chain,” the head of ICHCA comments.

Consequently, mis-declared VGM will continue to occur, as ports and terminals remain under-equipped, due to insufficient funds, with no external support. Moreover, there is a requirement for the authorities to make certain that there are similar penalties equally enforced for transgressions to the regulations.

Richard Brough again pointed to the absurdly low penalty fines, that he says are a key factor that is escalating the problem. In some European Union countries, the potential fine for VGM non-compliance is only US$325, while in the United Kingdom, the respective penalty can be as high as US$25,000 and/or a prison sentence.

The variation in penalties is huge and it is obvious that a shipper has no fear of being penalised in the low penalty jurisdictions, as the fine is ridiculously low, but the UK penalties could make a difference.

“One large exporter told me they will simply carry on doing what they did before,” Brough revealed to Container News.

This situation constitutes a problem, which extends the non-compliance issue even to the properly equipped ports and terminals in developed countries.

This issue is not, however, about the rich versus the poorer nations, but more significantly about the willingness for the industry to address the issues presented by the VGM regulations.